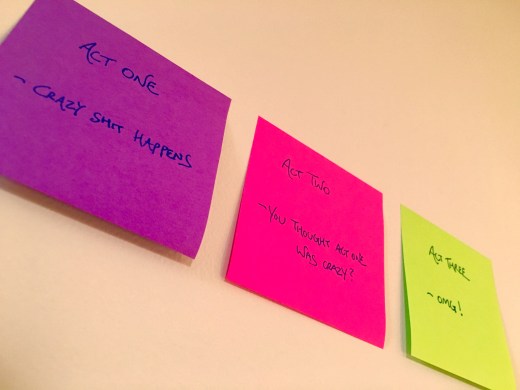

When you first start writing your script, you should censor… nothing! Let the ideas flow, let the characters do something crazy. Think big, dream big… all that good stuff.

You need to get all Field Of Dreams up in here…

When you’ve finished that first draft though, you’re going to need to switch out of writer mode and put on a different hat.

Spoiler: there’s more than one hat

Several hats, actually. The first is your editor hat. With any type of writing, you need to go over your work and approach it with unnerving, surgical precision, cutting away and removing things that you couldn’t possibly imagine losing but that the piece will be much better without.

You, editing

It’s often brutal, always necessary. If something is slowing your story down, making it too long, or is tonally off — snip snip! Once you have a tight script, in which every word is weighted with pivotal importance, it’s time for a wardrobe change as you look for your set designer hat.

This is where you have to evaluate your script on the basis of what the director (spoiler: this is you just with a different hat) can actually, practically shoot. This means dealing with the reality of your situation. If you set your script in a cafe, or a store, or an airplane, do you actually have the ability to (a) shoot in a real cafe, store, or airplane, or (b) recreate the interiors you need using creative set design (see our previous post)?

Shooting in a real location, such as a cafe or store, involves getting permission from the owner and working out all the details with them. Most will only let you film after hours for a set period of time, and they may insist their employees are present to keep an eye on things… which could be costly. They may let you use the location but not their materials — meaning you’ll have to bring in your own props (mugs, coffee machine, etc.). Along with props, you’ll need to bring in lighting and, if the script calls for them, extras. There are a lot of logistics involved with real locations, and depending what your relationship is with the owner, there could be insurance issues involved as well.

But don’t let this deter you!

The golden rule of making short films is that it NEVER hurts to ask. Just be polite and make sure they are comfortable with every aspect of your set and production. Don’t paint a wall or move a table without clearing it with the owner first.

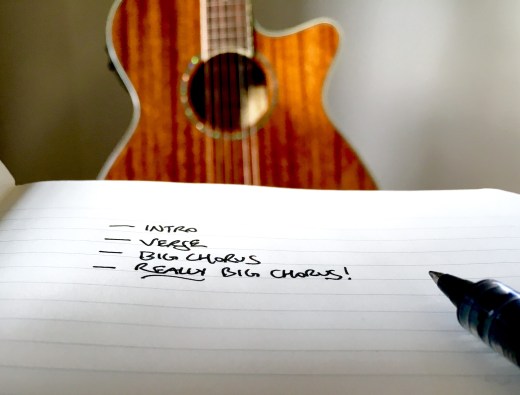

If you do manage to make a deal and secure a real location, and get the limitations worked out, you’ll have to put your director hat back on (retroactive spoiler: you were wearing your producer hat in the last couple of paragraphs) and work out your shot list. That’s basically a list of all the places you want to point your camera — we’ll cover that in a later post. A shot list will help you as the set designer figure out what will be in the scene. If it’s not exactly as the script described — you can’t have your lead character cleaning out the uber-expensive espresso machine because part of the deal with the owner was no touching anything that cost more that the coffee you were buying the cast and the crew — then you’ll have to change your script.

Sometimes it’s as simple as a tweak to an action sequence (e.g. instead of running across rooftops, your chase takes place on the street), but if that espresso machine represented all your character’s hopes and dreams of one day moving to Italy (and your short was a beautiful yet melancholic ode to the poetic symbolism of said machine, which actually sounds kind of cool!), you’re going to have some serious rewriting to do.

It’s so pretty…

Being unable to get a location you were hoping for, like getting turned down by American Airlines to make your movie on a 747, doesn’t mean you have to toss your script out the window. First, that’s littering and we would never encourage that, and second, it’s all part of the process, baby. With your set designer hat back on, you’re going to have to look around at what you can do. Is it possible to recreate the interior of an airplane? How about just the tiny space where the flight attendants hang out as they load the drink cart and talk about that rude bastard in row 23. All you need is a cart and a ridiculously small room.

If your original script had a flight attendant who’s scared of heights walking down the aisle, dealing with one flyer after another as she/he rolls past the rows, you’ll have to put your writing hat back on and change the dynamics without losing the tone, or the essential point of your story (it’s surprising how well the point of your story can survive intact through huge rewrites). Having the flyers approach the attendant as they load the cart instead could be a quick solution, but if it’s not as funny, or seems too contrived, you’ll have to dramatically change the scene, and possibly even aspects of the characters. If you changed the setting to a bank, for example, where customers are more likely to approach a teller, your bank teller being afraid of heights wouldn’t be so impactful, and any callbacks to that fact would have to be removed from the script: anytime you make changes, it’s a ripple effect.

Any excuse to reference Jurassic Park…

This is the messy art of rewriting.

Seriously, it’s messy

Sometimes you might need to lose the scene altogether. In that case, you’ll have to make sure the important information in any cut scene is dispersed throughout the rest of the script. Keep in mind that you may also need to adjust the scenes before and after the cut scene, so that your story still flows (ripple!). And watch out for any callbacks to that lost scene. If you edit out a set-up, you need to take out the payoff too. You might even need to create a new scene to replace the one you lost. If you can reuse a set that is already booked or built, all the better for the set designer (which is still you, by the way).

As a writer, it can be extremely soul-crushing to have to change your vision to cater to the pain-in-the-butt reality of the situation (#writerslife). But don’t give up. Ever. Try to be open to all the possibilities. You might have written a REALLY cool fight sequence in a train station, but thanks to ‘security concerns’ you weren’t allowed to film it. Exchanging that scene for one in which your character stumbles out of the station doorway, covered in blood, clothes torn up, could be all the action you need. Add a few words to another character about the fight and you’ve taken a logistically challenging three minute scene and turned it into a 30 second scene that was simple to shoot. Nothing of the plot was lost, and your film is now tighter.

Short films: the art of the shortcut.

Setting isn’t your only potential obstacle though. If you’ve written a key part for a 6’4″ lady with extreme martial arts skills and the ability to trapeze (because, you know, your short is called Circus Ninja 3)… kudos for the creativity, but get ready to rewrite the part if you can’t find an actress with the physical look and skill set to do that. Gwendoline Christie just might not be available, sorry! Depending on your pool of available actors, you may not be able to find someone to fit that role, so you grab your casting director hat. It fits snugly over your writer’s hat, don’t worry.

As casting director, you have to remember that it’s far more important to get the best actors you can to really make your lines sing. As a writer, you’ll need to zero in on what is important about your character, and find an actor who can work with those aspects and make them their own.

Rewriting your short film can seem overwhelming, especially when you started out with an in-air action movie about a vertiginous flight attendant and her extremely tall arch-enemy who works at the circus… and it then becomes about a bank teller fighting a spirited average-height nemesis who studied judo for a few months. Your new version will still have a comedy and truth all its own; all your own. The key thing to remember throughout the rewriting process is that operating with restrictions can spark your creativity even more (there’s a reason you could write a 5000 word term paper the night before it was due), whether it’s with set design, casting, or shooting.

Embrace these moments as you work towards making and finishing your short as opportunities to make your script even better.